I’m still boiling chicken feet! Last time I introduced the concept of eating gelatin to benefit joints, with the goal of maximizing the amount of gelatin extracted from chicken feet.

What exactly is gelatin? Here’s what my college biochem text [1] had to say: gelatin is denatured collagen. Collagen is protein that’s been bundled together to be very strong.

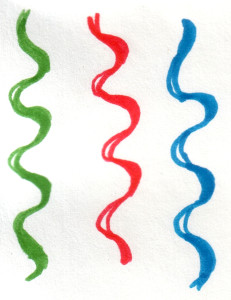

Start with three protein chains that are twisted into helices. These twists are left-handed. The three twisted proteins then twist together into a triple helix (also called a super helix, which if you ask me is way more exciting sounding) that is right-handed. This super helix is sometimes called collagen, but because further bundling occurs, one strand of the super helix is also called tropocollagen. (Tropocollagen is the building block in bundles of collagen.) Each tropocollagen is about 280 nm long. [2]

The form of a strand of collagen, with the opposing twist directions, is mirrored in rope-making: pulling on it won’t cause it to stretch longer and longer because of the opposing twists. It has tensile strength. The force of pulling in the long direction results in a compressive force inwards, perpendicular to the pulling.

Another note about collagen is that its amino acids repeat regularly. Every third amino acid is glycine, which is necessary because glycine is small, and it is squashed into the center of the super helix. Proline and hydroxyproline are also found, positioned so that their bulky rings are sticking out from the structure. Hydrogen bonds stabilize the helices.

Tropocollagen units bundle into a fibril. The units line up head-to-tail so that the spaces between them are staggered, which results in a banded appearance. Covalent bonds form between tropocollagen strands (near the ends of the strands) and stabilize each fibril. They also form between fibrils. These covalent bonds increase with time, which is why older animals produce tougher meat.

Collagen fibrils are in all the tissues in the body: skin, bone, cartilage, blood vessels, and more. They have different arrangements depending on their function. For example, in tendons (which must resist force in one direction) the fibrils are aligned parallel to each other. In skin (which must resist force in two directions) they are positioned at many angles and form layered sheets. And in cartilage (which must resist force in all directions) they have no regular arrangement.

So, what about gelatin? The book contains these magic words: “Collagen denatures at 39℃ [102.2℉]. Denatured collagen is called gelatin.” So all I have to do is heat above 102.2℉ and voila, gelatin? My other source states that the super helix breaks down at 60-65℃ [140-149℉] in mammals. Is there a magic number? And, does prolonged boiling destroy the gelatin, as some recipes seem to imply?

Next time, I’ll share what I’ve learned from research articles. In the meantime, I will try extracting gelatin using a pot of water at around 140-ish ℉. (So far, every stove setting has either resulted in the water boiling or turning cold….)

Here are the results of my most recent attempt in the kitchen:

4. My fourth attempt to extract gelatin used 8 chicken feet in 2 quarts of water and 1 Tbsp of vinegar. I decided to pre-boil the feet because I liked the idea of cleaning the feet this way, so I brought them to a boil, then dumped the water, rinsed the feet, and returned them to the pot with the measured water/vinegar. The pot cooked for 9 hours total, and the temperature moved between 170 and 212: the liquid either did the “one-glug simmer” (i.e., bubbles rise to the surface one at a time, in one location) or a gentle boil, but never a rapid boil. The stock cooled to form a gel with the consistency of pudding: a spoonful would stand up, but I could pour it from the container. Also, it was a clear golden color and had less funky of a taste, which I’m guessing is because of the pre-boil.

A spoonful of gelatin… well, it doesn’t exactly make the medicine go down in the most delightful way. Note: this photo was taken after cooling.

The stock resulting from this attempt was clear and golden. Note: this photo was taken before cooling.

[1] Voet, Donald and Judith Voet. Biochemistry. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1990, 159-164.

[2] Belitz, H.-D., W. Grosch, P. Schieberle. Food Chemistry (4th revised and extended ed.). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2009, 577-584.